Introduction:

Patients with increased blood pressure (BP) with various consequences (end organ injury) with a bad prognosis have been referred to as having malignant hypertension. Individuals who appear with extreme blood pressure rises are referred to as having a hypertensive crisis.

• Systolic level above180 mm Hg

• Diastolic level above 120 mm Hg. (Naranjo et al., 2019)

Hypertensive crises and hypertensive urgency are additional classifications for the diagnosis when a notable rise in blood pressure is associated with end-organ damage. The goal with malignant hypertension is to get the blood pressure down in a few of hours. (Medscape, 2020)

Examination:

A physical examination typically reveals:

● Abnormally elevated blood pressure

● Swelling of lower limbs

● Atypical cardiac rhythms and pulmonary fluid

● Modifications in reflexes, perception and thought

● Retinal bleeding

● The retina's blood vessels narrowing

● The optic nerve swells. (Domek et al., 2020)

Causes and Risk Factors:

● Adrenal diseases such as pheochromocytoma, Cushing's syndrome, Conn's syndrome, or tumors that secrete renin.

● traumatic brain damage, stroke, or brain bleed.

● Drugs and alcohol

● Renal artery disease.

● Cardiac structural disease.

● Thyroid problems. (Verywell Health, 2023)

Symptoms:

● Reduced production of urine.

● Hallucinations.

● Headaches.

● Diminished back discomfort.

● Shifts in mood.

● Vomiting and nauseous.

● Dyspnea, or shortness of breath.

● Changes in eyesight, such as blurriness. (Naranjo et al., 2019)

Diagnosis:

Your symptoms will determine the kinds of tests you undergo, which might include:

● A chest X-ray, which aids in identifying indications of pulmonary edema, or retention of fluids in the lungs.

● An electrocardiogram (EKG) to look for irregular heartbeats.

● Examining the eyes to look for evidence of bleeding or injury.

● Neurologic examination to assess brain activity.

● Physical examination, including measurements of both arms' blood pressure.

● A toxicology screening to determine the kinds of medications you take. (Medscape, 2020)

Tests:

● Analysis of arterial blood gas

● Blood urea nitrogen, or BUN

● Creatinine

● Analyzing urine

● Ultrasound of the kidney. (Domek et al., 2020)

Epidemiology:

Hypertensive crises are rare, occurring 1–2 times per million year, according to estimates. However, a recent study found that the rate per million adult ED visits and the expected number of ED visits for this condition more than doubled between 2006 and 2013. Eclampsia (2%), stroke of the brain (39%), and severe pulmonary edema (25%) are a few instances. (Naranjo et al., 2019)

Pathophysiology:

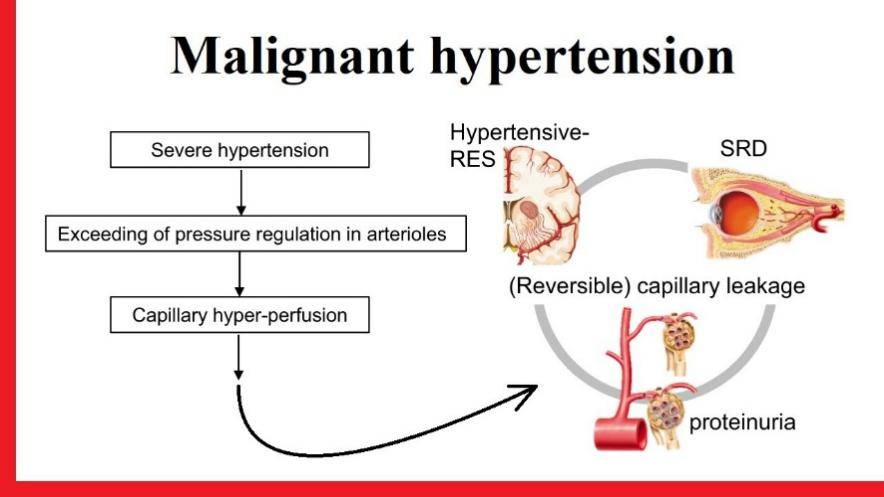

Hypertensive crises arise when a comparatively quick raise in blood pressure occurs in a little amount of time. The most recurrent causes of end-organ impairment are an upsurge in systemic blood vessel resistance due to renin-angiotensin activation-induced vasoconstriction mechanisms, pressure urination, hypoperfusion, and ischemia. (Medscape, 2020)

Fibrinoid apoptosis of the minor vessels is a characteristic of typical vascular disease. Furthermore, as red blood cells move through these blocked arteries, they frequently get destroyed, which can result in microangiopathic hemolytic anemia. The lack of brain autoregulation, which might manifest as hypertensive encephalopathy, is another characteristic of a hypertensive crises.(Domek et al., 2020)

Treatment:

Nitroprusside is the most often administered intravenous medication. Intravenous fenoldopam is an option for people with renal failure. Another popular substitute that makes the switch from iv to oral dosage simple is labetalol.

Intravenous calcium blockers, such as nicardipine, appeared to be more successful than intravenous labetalol in rapidly and safely bringing blood pressure down to goal values.

Metoprolol or esmolol can be injected intravenously to achieve beta-blockade. Enalapril, verapamil, and diltiazem are also administered parenterally. Hydralazine should only be administered to pregnant patients.(Medscape, 2020)

Prognosis:

Patients experiencing malignant hypertension have a cautious outlook. With therapy, reports of five-year survivals ranging from 75% to 84% were made; in the absence of treatment, life expectancy is fewer than 24 months. Heart failure, strokes, or renal failure account for the majority of fatalities. (Domek et al., 2020)

Complications:

Acute kidney damage, dissecting aortic aneurysm, encephalopathy, hemorrhaging cardiac arrest, acute heart failure, edema of the lungs, unstable angina, and vision loss are just a few of the consequences that might occur when target organs are impacted. (Verywell Health, 2023)

Conclusion:

Patients diagnosed with malignant hypertension are sent to an intensive care unit (ICU) to receive intravenous antihypertensive medicines and fluids, as well as periodic assessments of their neurologic state and urine output.

Patients usually have abnormal blood pressure (BP) self-regulation, and excessive BP reduction to reference range values might cause hypoperfusion in vital organs.

References:

1. Naranjo, M., & Paul, M. (2019). Malignant Hypertension. Nih.gov; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507701/

2. Malignant Hypertension: Background, Pathophysiology and Etiology, Prognosis. (2020). EMedicine. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/241640-overview

3. Domek, M., Gumprecht, J., Lip, G. Y. H., & Shantsila, A. (2020). Malignant hypertension: does this still exist? Journal of Human Hypertension, 34(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-019-0267-y

4. What Is Malignant Hypertension? (n.d.). Verywell Health. Retrieved December 1, 2023, from https://www.verywellhealth.com/malignant-hypertension-5525260

WRITTEN BY Checkme

Related Blogs

Recommended Products

Subscribe for special promotions,

healthy knowledge, and more!